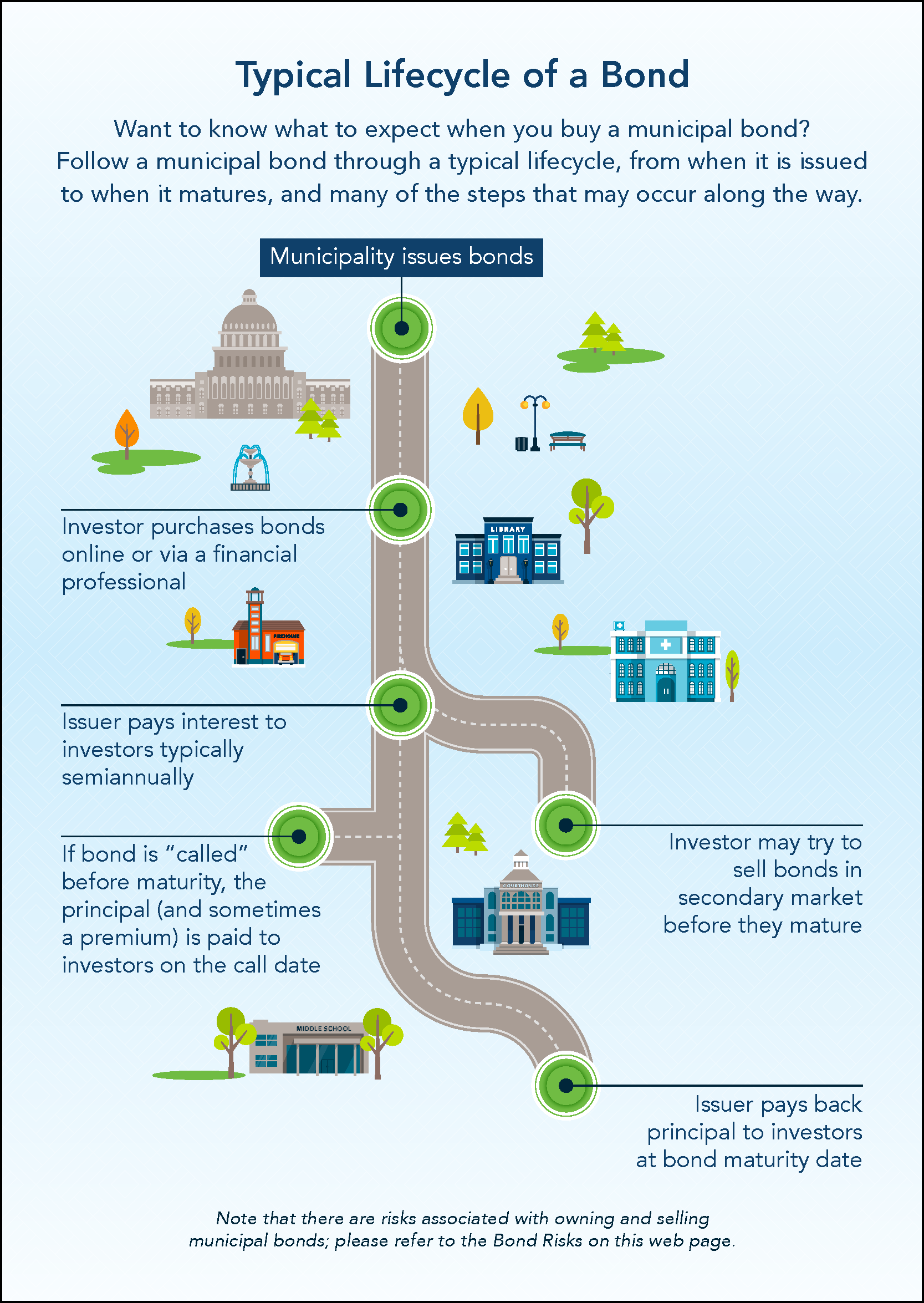

Municipal bonds are debt obligations that states, cities, counties and other public entities issue to finance infrastructure projects such as building schools, highways and sewer systems, as well as to fund the issuer’s day-to-day obligations. When you buy a municipal bond, you are lending money to the issuer in exchange for a promise of regular interest payments and the return of the face value of the bond (the “par value”) at the bond’s maturity date. Millions of U.S. taxpayers buy municipal bonds either directly or through separately managed accounts, or they buy mutual funds and exchange traded funds that invest in municipal bonds. See Ways to Buy Municipal Bonds to learn more about purchasing municipal bonds.

Bond Types

Most municipal bonds are fixed-rate bonds, meaning they pay a fixed rate of interest until maturity or earlier if the bonds are redeemed prior to maturity. The two most common types of municipal bonds are:

General Obligation (GO) Bonds, which are backed by the “full faith and credit” of the issuer, which has the power to tax residents to pay bondholders; and Revenue Bonds, which are backed by revenues from specific projects, such as toll roads or bridges, airports, electric and water utilities, public or private colleges, and hospitals, among other projects. Municipal issuers sometimes issue a type of revenue bond, known as private activity bonds, on behalf of private entities that are unable to issue tax-exempt debt on their own to finance certain types of projects such as healthcare facilities, affordable housing and educational facilities. In these cases, the public entity acts as a “conduit issuer” on behalf of the borrower but does not take responsibility to pay or guarantee the payment of the bonds. Instead, the borrower, known as the obligor, is ultimately responsible to pay interest and return the principal on the bond. Another less common form of municipal bond pays interest based on a variable rate. The most common type of variable rate bonds are variable rate demand obligations (VRDOs). VRDOs are long-term securities (e.g., maturity dates of 20–30 years) with short-term interest rate periods that are reset periodically. VRDOS are typically purchased by institutional investors. | Image

Click to enlarge |

Tax Status

Municipal bonds are generally referred to as tax-exempt bonds because the interest earned on the bonds often is excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes and, in some cases, is also exempt from state and local income taxes. Given the tax benefits, the interest rate for tax-exempt municipal bonds is typically lower than that on taxable fixed-income securities, such as corporate bonds and even Treasury bonds.

Not all municipal bonds are tax-exempt. For interest on a municipal bond to be exempt from federal income taxes, the issuer must meet several requirements in the federal income tax code. For interest on a municipal bond to be free from state and local taxes, the buyer generally must be a resident of the state where the bond was issued, although there are exceptions.

Municipal issuers sometimes issue taxable bonds if the purpose of the issuer’s financing does not meet certain purpose or public use tests under federal tax rules. And certain municipal bonds, such as private activity bonds, are subject to the federal alternative minimum tax (AMT), which means an investor’s interest income could be included in the calculation of the investor’s AMT. The yields on AMT bonds are higher, reflecting the risk that they could become taxable to some investors at some point in time.

Bond Features

Bonds have features beyond their tax status that are important to understand.

Par Value, or face value, is the amount of principal an investor will be paid at the bond’s maturity. It is usually expressed in multiples of $1,000.

Coupon Rate is the annual interest rate that the investor will receive on a bond. It is expressed as a percentage of bond principal. Municipal bonds typically pay interest semiannually.

Maturity is the date the principal of a municipal security is payable to bondholders unless the bond is redeemed prior to maturity (see Call Provision). Municipal bond maturities often range from one year to 30 years.

- “Serial” bonds are groups of bonds with a series of maturity dates typically occurring each year for up to 20 years.

- “Term” bonds come due in a single maturity whereby the issuer may agree to make periodic payments into a sinking fund for mandatory redemption before maturity or for payment at maturity. They typically mature after 20 years.

Denominations Fixed-rate municipal bonds are typically sold in minimum denominations of $5,000. VRDOs, however, typically have higher minimum denominations requiring a minimum investments of $100,00, which is why they are usually purchased by institutional investors.

Dollar Price is the dollar amount an investor pays to buy a bond. Bond prices are expressed as a percentage of the face value of the bond. A bond can be priced at par (100%), at a premium (above par) or at a discount (below par). A bond’s interest rate and maturity will affect the price an investor pays for the bond.

Call Provision is an early redemption provision that allows the issuer to redeem the bond before the stated maturity date at a specified price. The bondholder receives the principal amount of the bond and, in some cases, an additional premium. Many municipal bonds have call provisions, although most of these bonds cannot be called before a specified period, such as 10 years.

Yield is the annual return an investor receives on a bond, based on the purchase price of the bond, its coupon rate and the length of time the investment is held.

- Yield to Maturity is the total return an investor expects to receive from holding a bond to maturity.

- Yield to Call is the rate of return the investor receives presuming the bond is retired/redeemed on the call date (see Call Provision).

- Yield to Worst is the calculation producing the lowest yield that can be received on a bond incorporating an early redemption or call provision. Yield to worst is often the same as yield to call for bonds priced at a premium because there is less time for the premium to be amortized. Conversely, for a bond purchased at a discount, the yield to worst is typically the same as yield to maturity. Yield to worst is the yield that must be reported to investors on their confirmation when they buy or sell a bond.

- Current Yield is the ratio of the annual dollar amount of interest paid on a bond to its purchase price.

Security for the Bonds. Bonds are payable from specific sources, ranging from the general taxing power of the issuer (as in general obligation bonds) to more limited taxes (e.g., sales tax revenues) or revenues produced from a project (e.g., sewer system revenues). In some cases, bond insurance, a letter of credit guarantee or other credit enhancement may exist to support repayment of bonds. Security for the bonds is key to assessing credit risk, as discussed in Bond Risks.

Credit Ratings. In many cases, but not always, the issuer may receive a credit rating for its bonds. A credit rating is an evaluation that rating agencies such as Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, Fitch and Kroll Bond Rating Agency assign to a bond to indicate the likelihood that an investor will receive principal and interest payments from the issuer in a timely manner. Credit ratings represent the opinion of the rating agency and not a statement of fact or recommendation to purchase, hold or sell a security, and they can change during the life of the bond. To learn more about credit ratings, see Credit Rating Basics for Municipal Bonds on EMMA.

Bond Risks

Municipal bonds are often considered a safe investment; however, the return of principal and interest is not guaranteed. In fact, some municipal bonds, such as high yield municipal bonds, may be risky. Investors need to review the specifics of the bonds they are considering or already own to evaluate their risk. Some of the main risks associated with investing in municipal bonds include credit/default risk, interest rate risk, call risk and reinvestment risk, among others. To learn more about risks associated with investing in municipal bonds, see Municipal Bond Investment Risks.